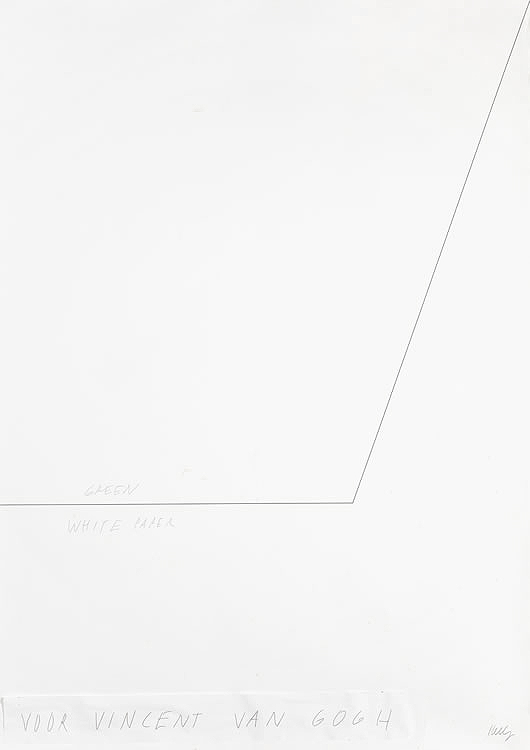

Voor Vincent Van Gogh

1989-1990

Signed and titled ‘VOOR VINCENT VAN GOGH Kelly’ (lower edge)

Graphite and paper collage on paper

46 ¼ x 32 ¾ inches (117.5 x 83.2 cm.)

Ex-collection:

Private collection, Netherlands, acquired directly from the artist

Anon. sale; Grisebach GmbH, Berlin, 1 June 2012, lot 689

Private collection, New York

Note: This work the study for a poster by Kelly created in the same year 1989-1990

On Halloween night in 1935, in rural Oradell, New Jersey, the twelve-year-old Ellsworth Kelly was trick-or-treating with friends in their neighborhood after dark. Upon approaching a house from a distance, he said: “I saw three colored shapes—red, black, and blue—in a ground-floor window. It confused me and I thought: ‘What is that?’ When I got close to the window, it was too high to look in easily and I didn’t want to be peeking. I was very curious and came at the window obliquely, and chinned myself up, only to look into a normal furnished living room. When I backed off to a distance, there it was again. I now realize that this was probably my first abstract vision and the path was set. Kelly’s first homage to Van Gogh was done in 1948 before leaving for France, The work titled “Shoes” (1948), in which drab footwear, strewn hither and thither, coalesce into accidental harmony. One of his last purely realist works, “Shoes” prefigures the way Kelly would go on to pair chance operations with an assured selectivity. As his signature style matured it became apparent that dualistic approach would become Kelly’s blueprint. There are shapes or color combinations that one has failed to notice because, in order to perceive them one has to forget the image—something Kelly can do effortlessly, because the real background against which these shapes and color combinations stand out for him is not the picture from which his perception excerpts them but the vast mental storage in which he keeps everything his matrix has produced, including, tiny little sketches made years before for paintings, reliefs, or sculptures that were not realized. As per Yves Alain Bois who recalls while visiting an exhibition of van Gogh’s portraits in his company and hearing him associate a detail of one of the canvases on view to one of his recent works, that he should make sure to remember that van Gogh had not copied him. (Though in fact one could say that van Gogh is in debt to Kelly—not van Gogh the long-dead man, but van Gogh the oeuvre as we see it now—benefiting from Kelly’s work as well as from that of many other artists of the twentieth-century. But that is the story of modernism as a whole. More importantly, perhaps, is the fact that the line in VOOR VINCENT VAN GOGH is itself an involuntary accident, almost like a hiccup or a Freudian slip of the tongue—the sudden “apparition” of a shape as it strikes a chord for being unrecognizable, for being recognized as something the artist consciously knows it is not. Either this shape echoes something already caught in the web of the matrix, or it appeals to Kelly for its potentiality as a score for a new piece, but a score whose material performance in the real world, an “already-made” unperceived by anyone but him, is only the material proof that it can, indeed, exist on its own.

Voor Vincent Van Gogh

Voor Vincent Van Gogh