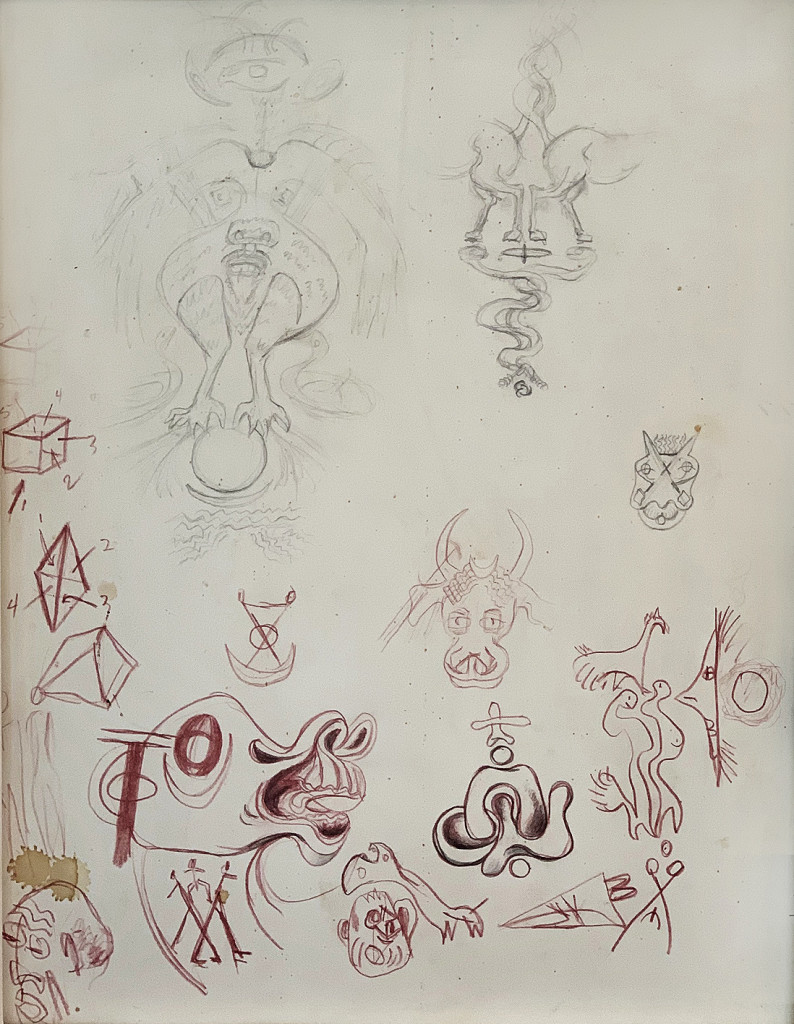

Untitled

ca. 1939-40

Red pencil and pencil on paper

14 x 11 inches (27.9 x 35.6 cm)

Ex-collection

The Artist

Dr. Joseph L. Henderson

Maxwell Galleries, San Francisco CA

Hoover Gallery, San Francisco CA

Private Family Trust, San Francisco, CA

Nielsen Gallery, Boston MA

Private Collection

Exhibitions

Maxwell Galleries, San Francisco, 1970

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, October 12-November 15, 1970

San Francisco Museum of Art, California, January 6-February 10, 1971

Santa Barbara Museum of Art, California, March 1- April 2, 1971

Fine Arts Gallery of San Diego, California, July 3-August 8, 1971

Phoenix Art Gallery, Arizona, September 7-October 17, 1971

Isaac Delgado Museum of Art, New Orleans, Louisiana, January 1972

Milwaukee Art Center, Wisconsin, May 1-31, 1972

Berry-Hill Galleries, Inc., New York, January 18-February 5, 1977

Jackson Pollock: “Psychoanalytic Drawings,” Duke University Museum of Art, Durham, North Carolina, January 31-March 29, 1992

Literature

Clyde Leo Wysuph, Jackson Pollock: Psychoanalytic Drawings (New York: Horizon Press, 1970), no. 65; illustrated b&w

F.V. O’Connor and E.V. Thaw, eds., Jackson Pollock: A Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings, Drawings and Other Works, v. 3, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1978, no. 523; illustrated b&w, 98

Claude Cernuschi, Jackson Pollock: “Psychoanalytic Drawings,” Duke University Press, 1992, 13-14; illustrated in color, plate 50, 97

Jackson Pollock’s metamorphosis from Regionalist to Abstract Expressionist, has been a source of fascination ever since his untimely death in a car crash in 1956 at age 44. A predisposition to restiveness, depression and alcoholism stemming from his unsettled childhood resulted in making Pollock into a painfully insecure, self-destructive and mentally conflicted adult, impaired in his ability to verbalize thoughts and emotions. By his late twenties, he required professional psychiatric treatment. Dr. Joseph L. Henderson, the first of his two Jungian analysts, with whom Pollock worked in New York in 1938-1939, recognized immediately that only by finding his own artistic identity would Pollock be able to overcome these issues.

Prior to consulting Henderson, Pollock had moved to NYC from California and, like his older brother Charles, studied at the Art Students League with Regionalist painter Thomas Hart Benton, famous for down-home “American” subjects painted in a Mannerist style. Accelerating creative blocks after Pollock left the League generated more violent swings between agitation and states of paralysis or withdrawal that led to his brief hospitalization in a mental facility. As another brother explained, it became imperative that Jackson figure out a way to “throw off the yoke of Benton” in order to create in a “more intense, evocative and abstract way.” Henderson suggested to Pollock bringing in his contemporaneous drawings as a means to provoke meaningful conversation. When he left for California after eighteen months, passing him on to another analyst, Pollock gifted Henderson the 69 drawings (13 double-sided for a total of 83) and one gouache used for discussion. A little more than a decade after Pollock’s death, Henderson (despite protests by the artist’s widow, Lee Krasner, that he was invading her late husband’s privacy) wrote about Pollock’s treatment and sold these works to the Maxwell Galleries in San Francisco. Maxwell showed them in 1970 accompanied by a book authored by C. L. Wysuph. This exhibition subsequently traveled to nine museum venues through 1972.

Interesting not only from a psychological point of view, these drawings, including Untitled (JPCR 523), also catalogue the diverse artistic directions Pollock had begun to explore in order to move beyond Benton’s style. In fact, as opposed (perhaps in addition) to referencing Jungian concepts or marking the totally unconscious production of subjective symbolism, they exhibit a strong dependence on imagery borrowed from famous artists, in particular José Clemente Orozco and Pablo Picasso, two painters Pollock passionately admired at this time. Pollock’s obsession with Picasso had developed as a natural step following his interest in the revolutionary Mexican muralists, of whom Orozco was his favorite. Both of these as key influences, and Pollock’s interpretation of their achievements, are evident in the iconography of JPCR 523.

Interestingly, Dr. Henderson paralleled Pollock’s psychological motivation to create drawings like JPCR 523 with the “states of mind ritually induced among tribal societies or in shamanistic states.” Indeed, allusions to Native American artifacts, another interest of Pollock (who was born in Cody, Wyoming and partly raised in Arizona) also appear frequently, including here. “The Indians,” Pollock believed, “have the true painter’s approach in their capacity to get hold of appropriate images.” Primitivistic iconography delineated on the lower half of this sheet, including human stick figures, metamorphic animals, a dagger and several somewhat less identifiable ideographic objects, all drawn in red pencil, easily relate to Native American reference points. Read left to right, like picture-writing, an enigmatic chain of associations is made more perplexing by Pollock’s insertion of numbered geometric diagrams at left and two realistic faces, one in the lower left corner, with a more comic version smiling at bottom center. No similar portraits appear in any of the other Henderson drawings. In particular, one is led to wonder who might be the balding man with open mouth and furrowed brow, and what role his specific visage may have played in Pollock’s state of mind as he created this work.

JPCR 523, part of a sub-series of the so-called “psychoanalytic drawings,” presents a group of smaller images with seemingly little or no obvious thematic relationship, all sharing the same pictorial space. Animal or monster motifs often predominate in this set, particularly variations of the horse and bull, two creatures already in Pollock’s “cast of characters” as seen in earlier paintings. Such animals now take on a more mutable form (even sometimes interacting with each other) in ways suggestive of Picasso’s sketches for Guernica, his 1937 masterpiece then residing in New York. These were widely reproduced by the time Pollock created the drawings he gave to Henderson. In addition to the Guernica sketches, the two bull heads in JPCR 523 also seem to reference Orozco’s Prometheus mural, of which Pollock saw in California, and later pinned a reproduction to his studio wall. Even more, they bear a strong likeness to symmetrically stylized bucrania, a common motif often seen on the Doric frieze. The larger wears a crescent moon ornament between his horns, a symbol Pollock may have discussed with Henderson as related to the gendering of the psyche, and his ongoing fascination with the Moon Woman, as well as other aspects of the lunar cycle, resulted in several important paintings of 1943. Perhaps an allusion to her is seen in JPCR 523 at far right in a Picasso-inspired profile, seemingly chased by her opposite, the masculine sun.

The most important foreshadowing of things to come appears at top left in JPCR 523. Sketched more faintly in lead pencil rather than red, the upper register of this sheet of studies includes two symmetrical and frontally stacked vertical designs. At right the rear flanks of two horses with braided tails float above identical sinuously entwined Orozco-influenced snakes. At left, a humanoid bird body with female innards and distinctive claws stands on an orb hovering atop an upturned crescent. All are placed over a set of wavy lines resembling heat rising from the ground or perhaps the sea. Instead of a head, a huge central eye crowns this hybrid creature. Once again, JPCR 523 stands apart from the other drawings that Pollock brought to his sessions with Henderson, as this section comprises an early study for the heraldic imagery of Bird, a key painting of 1941, also presaged by a more finished sketch given to his second psychiatrist. The latter pictures the transformation of a levitating shaman in the desert whose head is replaced by a prominent central eye. The version in JPCR 523 is much closer to the final painting which depicts a pigeon-toed cock or eagle with outspread wings now seen straddling a golden orb. A bright red fetus is disclosed at the center of its body and facing (bald) human heads border its legs on each side. A huge widely-opened eye floats above, identical to its 1939 study. Bird, as seen in JPCR 523, was first conceived at the time of Pollock’s analysis.

Ellen G. Landau

Andrew W. Mellon Professor Emerita in the Humanities

Case Western Reserve University

Untitled

Untitled

Untitled (The Family)

Untitled (The Family)

Untitled

Untitled

Untitled

Untitled