Embracing Arms (Upraised Arms)

1944

Bronze

Signed and numbered 2/6

19 1/4 x 8 3/4 x 7 1/4 inches

Ex-collection:

The Artist

Perls Gallery, New York

Private Collection

Rico Maresca Gallery, New York

Private collection until the present

Literature:

Calder, The Complete Bronzes, exh. cat., New York, L&M Arts, 25 October 2012-9 February 2013, no. 17 (another from the edition exhibited; illustrated in color, pp. 51, 110-111)

This work is registered in the archives of the Calder Foundation, New York, under application number A02650

This work is sold with the ink study for the bronze

In 1944, Alexander Calder’s friend Wally Harrison suggested that he make a series of large outdoor sculptures out of cement, an idea which, according to Calder, Harrison forgot about but Calder pursued, albeit it in a different manner. Entranced by the mutable characteristic of cement, Calder took the idea and made it his own. Instead of large scale outdoor pieces, he started work on a series of more intimate figural sculptures made in plaster. Calder notes, “I finally made things which were mobile objects and had them cast in bronze—acrobats, animals, snakes, dancers, a starfish, and tightrope performers. These I showed that fall at Curt’s [his then dealer Curt Valentin’s Buchholz Gallery in New York]… This was rather an expensive venture and did not sell very well, so I abandoned it for my previous technique.”1 In total, Calder created twenty-five individual and unique bronzes in 1944, many exhibited at Buchholz Gallery. Of those, it seems eighteen did not sell and Calder hid those away in basement of his mother’s Roxbury, Connecticut home, forgetting about their very existence until October of 1968. At the time of their inception and initial casting, Calder found the whole process to be somewhat intrusive and overly complicated in comparison to his already well-developed ritual of working by himself with sheet metal and wire. He stated, “It was also disagreeable to have to check the manipulations of some other person working on the objects at the foundry.”2 What changed between 1944 and 1968 is unclear, however, Calder was certainly pleased to have rediscovered the bronzes at this moment in his career. Aptly realizing that the bronzes would be received much more positively and magnanimously by his audience this time around, he had the 18 remaining bronzes recast in limited numbered editions of six by Roman Bronze Works Inc., of Corona, New York under the guidance and assistance of himself and Sculpture Services, New York. While the casting process was undoubtedly unnerving and tedious for Calder, he certainly recognized its appropriateness and relished the formal qualities of the material in relation to his subject matter. He notes, “Bronze, cast, serves well for slender, attenuated shapes. It is strong even when very slender.”3 In retrospect, bronze is likely the most ideal media with which to construct these small Surrealist forms, and certainly for one as delicate as the present lot. Embracing Arms, 1944-1969, is graceful and exuberant yet strident and balanced, firmly rooted to the ground in the weight of its medium. Each of the sculptural works from this series of bronzes exhibits Calder’s systematic approach to the exploration of space, balance and movement that his more common sheet metal and wire stabiles and mobiles investigate. More interestingly, however, is the more unique Surrealist quality that these works exude that at times gets lost in the mobiles and is perhaps more omnipresent in his myriad gouaches. When Calder first created the models for these works from plaster in the 1940s, his work resonated with the Surrealists, particularly Miró and Picasso. Calder’s exquisite early paintings and delicately balanced mobiles are highly reminiscent of the techniques that Miró and Picasso perfected. In Embracing Arms, however, the influence of these artists on Calder’s work becomes abundantly clear, especially when considered side by side with Picasso’s Nude Standing by the Sea, 1929. This comparison exemplifies Calder’s ability to expand upon a certain sort of Surrealist form to aid in his three-dimensional investigation of material, space, and momentum. Perhaps it was simply working with the new medium of bronze that provided the impetus for Calder to tackle his subject matter with a revised approach. As Roberta Smith writes in her review of L&M Arts Complete Bronzes show, “the ancient medium enabled him to move deeper into art history; to keep pace with and borrow from other more traditional strands of modernist sculpture and to use his hands and amazing tactile sense in a different way. The exhibition sheds new light on his complex sensibility while also showing him pursuing some of his characteristic interests — like levitation — in an unlikely material. In addition the play between the white plasters, which are so responsive to light, and their nearly identical twins in the dark, more matte bronze is fascinating.”4 Despite the initial less favorable reaction to these works, it is now, more than ever, evident that these works delineated a decisive evolution in Calder’s career—the bronzes themselves bridging the gap between his early and mature career. James Johnson Sweeney, perhaps one of the most important Calder scholars to this day, maintains that it was 1944 that hallmarked what art historian H.H. Arnason describes as the “most fertile and imaginative period of his creative life.”5 1. A. Calder, quoted in Alexander Calder, Bronze Sculptures of 1944, exh. cat., New York, Perls Galleries, 7 October-8 November 1969, unpaged. 2. Ibid. 3. A. Calder, quoted in “A Propos of Measuring a Mobile” (manuscript), Archives of American Art, 1943. 4. R. Smith, “Relics of a Sculptor’s Bronze Age: ‘Calder: The Complete Bronzes’ at L&M Arts”, in The New York Times, 8 November 2012. 5. H.H. Arnason, Calder, Princeton, 1966, p. 76.

Mephisto

Mephisto

Cat People

Cat People

Black Performer

Black Performer

Untitled

Untitled

Black Disc

Black Disc

Rising Sun

Rising Sun

Untitled

Untitled

Untitled

Untitled

Little White Polygons

Little White Polygons

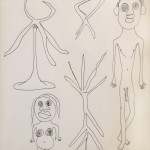

Untitled (Studies of Figures and Sculpture)

Untitled (Studies of Figures and Sculpture)

Embracing Arms (Upraised Arms)

Embracing Arms (Upraised Arms)

Untitled

Untitled

Untitled

Untitled

Kangaroo

Kangaroo

Ashtrays

Ashtrays

Ashtray

Ashtray

A Heart Brooch

A Heart Brooch

A Brooch

A Brooch

Untitled (Cape Clasp)

Untitled (Cape Clasp)

Necktie

Necktie

Untitled

Untitled

Rire Jaune

Rire Jaune

Skeleton Toasting

Skeleton Toasting

Red, Blue, Yellow Man

Red, Blue, Yellow Man

Loose Curls

Loose Curls

Little Miss Pocket

Little Miss Pocket

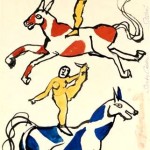

Saltimbanques

Saltimbanques

Smeary

Smeary

Untitled

Untitled

Untitled

Untitled

Untitled

Untitled

Swimmers

Swimmers

Red and Black

Red and Black

Untitled

Untitled

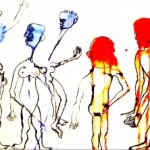

Blue People, Red People

Blue People, Red People

Black Spiral

Black Spiral

Fish and Faces

Fish and Faces

Study for the Universe

Study for the Universe

Untitled

Untitled

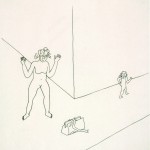

Rehearsal

Rehearsal

The Acrobats

The Acrobats