Willem de Kooning A Retrospective

July 2, 2011– July 22, 2011

-

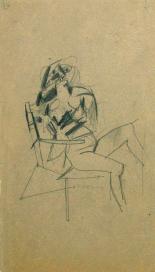

Willem de Kooning ( 1904-1997) Woman seated in chair (untitled # 32) c. 1950-53

Graphite on gray card 14 x 8.5 inchesThis exhibition features Abstract Expressionist Willem de Kooning’s studio sketches, and epitomizes the notion of art that stands on its own merit, and is particularly timely considering an upcoming full-scale retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, scheduled to open in September. The exhibition begins chronologically, spanning the artist’s oeuvre from the early 1940s, straight through the late 1960s, offering a penetrating glimpse at the progression of his visual language. The works begins with his early realist, figurative abstractions, to a “proto-synthetic cubism,” straight through the famous series of women that dominated the 1950s, ending in his increasingly “expansive,” looser renderings of the 1960s.

Of particular interest is a portrait sketch the artist produced of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, during the early days of the New York School and Works Progress Administration. The drawing (“Portrait of FDR,” 1940-44), a hyper-realist representation of the New Deal President, is far removed from the typical fragmented forms de Kooning is known for, demonstrating the artist’s skill as per the tenets of classical training.

“Probably the most libidinal painter America has ever had,” according art critic Robert Hughes, looking at de Kooning’s paintings, the way he immersed himself in the female form in his famous ‘Women’ series from the 50s, and the way the body — admittedly in pieces, but the sensual body nonetheless — returns, over and over again, we can’t help but agree with Hughes.

Born in Rotterdam, Netherlands, de Kooning emigrated illegally to the United States in 1926. Along with Jackson Pollack, he became a leading member of the New York School of Abstract Expressionism. De Kooning developed a distinctive, hallmark style, later termed action painting. Peter Schjeldahl described the technique as “an arm motion that unclenched one of the most concentratedly intelligent marks ever seen. The stroke could deliver at once line, shape, color, contour, depth, touch, rhythm, and, crucially, scale… you grasp the muscular eloquence, both fierce and delicate, of that visible exertion, which communicates between the artist’s body and your own… it’s as if he were holding you by the hand as all hell breaks loose around you.”

De Kooning’s paintings contain fragments of bodies that seem to emerge from the thickly applied paint, writhing against one another in an ever-increasing tempo — here an elbow, there a thigh, but nothing explicit, always just suggestions. They also contain fragments of pop culture. Film, advertisements, and iconographic images all find their way into his paintings.

In the 1980s, de Kooning began to suffer from the ravages of Alzheimers, but continued to paint for nearly a decade as his mind gradually descended into senility. Many of the paintings from this late period have stymied critics, for they are both evolutionary extensions of his previous work and something new. Although difficult to understand, the late paintings contain an undiminished power and excellence. Schjeldahl once again: “I propose that late de Kooning is the degree zero of painting, attained not through simplification but, fully complex, through being emptied of anything not identical with its execution. This work henceforth defines the verb ‘to paint’.